After the Mad Max, kill-or-be-killed, zombie apocalypse phase of SHTF has passed, the survivors will not emerge equal. There will be the new “rich” (the preppers) and the new “poor” – those who survived with little or nothing. With the vast “safety nets” of the modern welfare state gone, what do you do with the poor?

America in the 1700s and 1800s was a vibrant and growing nation. Yet, amid all the expansion and opportunity, there were still poor people. In the 1800s, there were no food stamps, Medicaid, Medicare, TANF, CHIP or Housing Assistance. How did the townsfolk back then deal with the poor people around them?

Tough Beans?

It is pretty easy or a prepper (today) to be dismissive toward the unprepared; like the Ants telling the Grasshopper, “Too bad for you. You should have worked. Go starve.” The trouble is, the new (post-SHTF) poor may not be limited to strangers or moochers, like the grasshopper, from “outside.” They might well be people you know and have some connection to.

Imagine that a fellow prepper family in your Mutual Assistance Groub was caring for their frail grandfather, but the family themselves are killed by robbers. Grandpa Smith survived. What do you do with Grandpa Smith now? Let him starve?

Imagine that a fellow prepper family’s father/husband/provider falls and breaks his back. He can no longer pull his weight. The family that depended on him can only compensate so much. Do you send Mr. Broken and his family into the outer darkness?

Imagine that the father and mother in a fellow prepper family die trying to put out a fire in their home. They had five kids who no longer have parents or a home to live in. Do you just tell the kids to move along and get off your lawn?

Dismissing the poor as not-my-problem, post-SHTF, may not be as easy as you think. For one thing, would you want that standard to be applied to you too?

The Three Types of Poor

First, it is important to recognize that not all of the poor are the same. Even in antiquity, people understood that there were three types of poor people. Their situations are not identical so their solutions would not be either. In the ever-popular Ant and the Grasshopper fable, the grasshopper was an able-bodied, but foolish wastrel. Not all poor people are foolish wastrels.

1. The Impotent Poor

Sometimes, through no fault of their own, a person might not be able to provide for themselves. People get too old for heavy labor. People get sick or injured and cannot work. What do the Ants do with them? Kick them out in the snow when they can no longer work? What do you do with your own ailing grandma or someone else’s grandma?

2. The Working Poor

Even hard-working individuals can take some bad breaks. Imagine a struggling subsistence farmer whose crops were wiped out by drought or hail. He then had nothing to feed his family. Or a tradesman (say, a miller) whose mill was destroyed by a flood. What do the Ants do with them? Tell them to pound sand?

Both of these types of poor folks seem deserving of some help. Both groups could not prevent their poverty. Charity for the first two types would be more comfortable if it were not for the third type of poor people.

3. The Idle Poor

These are people who are “poor” by choice. They game the system. A panhandler in Boston once told me he can “earn” $20 an hour shaking his cup on a street corner. Why should he work? Moochers seem to be a persistent problem.

The apostle Paul spoke about this problem in his first letter to the Thessalonians (verse 3:10) when he said that those unwilling to work should not eat. The early church in Thessalonica was generous in their support of the poor (the first two types). That generosity attracted moochers would not work, but just took the charity and sat around being busybodies.

In ancient Europe, regular care of the poor was undertaken by the church. Religious orders used some of the tithes given to the church to fund poor houses and gave alms to the needy. Indeed, most religions teach charity toward the poor (the first two types). Since the friars generally knew their parishioners, it was easier to differentiate between the deserving poor and the idlers.

Later, towns would take over the role of dispensing charity. Often a tax was levied on citizens for the care of the poor. Various kings of England issued proclamations prohibiting the giving of alms to the idle poor. Every age, it seems, had its moochers and freeloaders eager to live off of someone else’s labors. Reagan’s “welfare queens” were not a new problem.

“The poor you will always have with you,” Jesus said. How did people deal with the poor before the modern welfare state?

First Safety Net: Family

Long ago, it was more common for fathers, sons, cousins, uncles, etc., to live near each other in extended families. Familial love has a ‘no man left behind’ ethos. They usually took care of their own sick, injured, elderly, and even their own mentally ill. Modern mobility has fragmented the extended family. Caring for family poor became a burden shared by fewer and fewer family members.

Sometimes, however, even a limited family were not available. Disease and disaster could leave individuals as the last of their family. If the “last” family member was not fully fit and capable, care fell to the community.

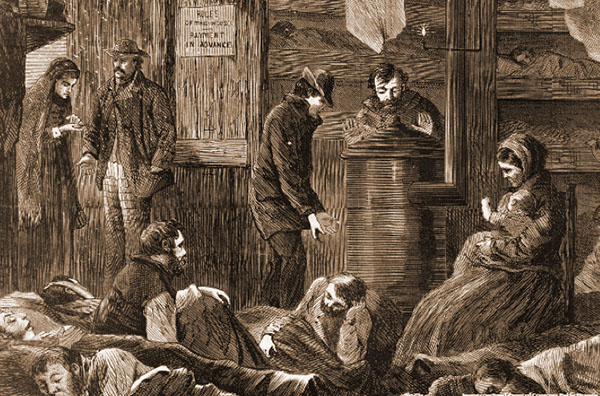

Alms Houses, Poor Houses

One way that people dealt with the impotent poor was to concentrate them in one place to make caring for them more efficient. Poor Tax funds were collected to purchase their food and clothing. Poor houses tended to be a mixture of part old-folks-home, part homeless shelter, part infirmary, and part insane asylum.

Workhouses

In industrialized areas such as Victorian England or the American northeast, workhouses provided a way to handle the working poor as distinct from the impotent poor. Those who could work were expected to.

Those down on their luck but healthy enough to work would be given labor to do in exchange for room and board. The work was often harsh, like breaking up rocks, grinding corn or crushing gypsum. Those running the workhouses did not want them to be comfortable. That would only attract moochers. They were intended to be half safety net and half deterrent. The intent was to encourage people to be diligent and cautious to avoid workhouses.

Auctioning

Before the poor houses and workhouses, one method used during the 1700s and early 1800s for the care of the impotent poor was Auctioning. If the town did not operate a poor house, they would auction off a poor person to the lowest bidder. Town selectmen might, for example, ask at a town meeting what someone would charge (the town) to take in an elderly widow. The lowest bidder would “win” the stipend and the old widow who would then be moved into the winner’s home.

While modern sentiments might chafe at the slavery overtones of auctioning, those who were auctioned were not the working poor. They could not labor, so they could not really function like slaves. They were simply dependents. The plus side was that an old widow would be put up in someone’s home instead of living alone. The auctioned person might be mistreated (think Cinderella) or they might be like an extra grandmother.

Post-SHTF, a community might seek to distribute its impotent poor among households that could provide a roof and meals. We could see the return of Auctioning.

Binding Out

Somewhat closer to the slavery model was a practice called Binding Out. It was generally confined to orphans and usually boys. Orphans were a lot more common in the old days — and they might be more common post-SHTF. The father could die of an injury, or sickness (or killed by robbers). The mother could die of childbirth or disease, etc. Post-SHTF, there could be many real orphans. Poor houses for children (an orphanage) were a mixture of impotent poor (kids too young to work) and working poor (kids who could work).

To ease orphanage populations, the selectmen would enter an agreement with a family (the Binding) to take in an orphan (Out of the orphanage). These children would mainly be indentured servants to the host families. In theory, the host family agreed to care for the child and teach them a trade (apprenticing).

While Binding Out had its abusers, it was often a step up for the child to be living in a family home instead of the orphanage. A family’s biological children in the 1800s were workers too, so the Bound Out child was not the only child laboring in the family. When the child turned 18 or 21, they were released from the Binding.

Post-SHTF, orphan children could get assigned to particular families. They would be expected to work, just like all the other family members, in exchange for their room and board.

Town Farms

A rural New England variation on England’s workhouses were Town Farms. The town’s selectmen would buy a farm and settle the town’s poor there. The working poor were expected to do the work of the farm to provide for everyone. The infirm were often able to contribute to a lesser degree — such as old women spinning fibers into yarn, washing, cooking, etc. Even the mentally handicapped or mentally ill were often able to contribute in some way.

With the inefficiency of an excess of labor (and limited skills), Town Farms seldom turned a profit or even provided everything for their own upkeep. They did tend to cost their communities less than mere Poor Houses. Having work to do was better for morale than inactivity. An advantage to the Town Farm was that the operators knew their residents. It was a lot easier to identify the moochers.

Post-SHTF, a collective farm or workhouse could be where the new working poor could be housed and work for their room and board. If so, it would be good to figure in some way for the worker-resident to profit from their labors and eventually earn their way out. If they labor only for room and board, they will (a) never leave and (b) have no incentive to work hard.

Ordering Out

The Idle Poor were sometimes ordered out of town by the selectmen. This was sometimes referred to as “Warning Out.” The vagrant was warned that sterner measures would be taken if they did not leave town. Due to an old feature of English law called the Settlement Laws, the town where one was born, or resided in officially, was the town deemed responsible for you. Since the Idle Poor tended to drift around looking for the best mooching deal, it was not uncommon for the selectmen to order the moocher out of town, back to their “settlement” town. While this practice tended to devolve into various towns all denying that Mr. Idle was one of theirs, it did tend to kick the moochers out of town and get them moving on to some other town.

Post-SHTF, a community will need to have and enforce some vagrancy laws. If a community is at all successful in rebuilding after the collapse, that success will attract moochers like flies to honey. The odds are strong that you will have to force some idle poor to leave your area. Figure out how you’re going to do that now rather than making it up on the fly later.

Post-SHTF and The Three Types of Poor

After a major collapse, there will still be all three types of poor people for the prepper survivors to have to deal with.

There will be those Impotent Poor who just cannot pull their own weight: sick, injured, old, etc.

The Working Poor might be the more common poor folks after SHTF. These would be the hundreds of thousands of sheeple who only have virtual wealth in Ones and Zeros, grid-dependent job skills and no supplies. After “The Event” they will be destitute. Yet, they are still able to work.

There will, of course, be the moochers. Our society is chock full of such folks right now. Post-SHTF, many moochers will seek ways to continue to have someone else provide for them so they can continue to be comfortably idle. If the government will no longer support them, they’ll seek new sources. That could be you. Most preppers I’ve spoken with have a strong distaste for moochers. Idlers can expect a harsh reality post-SHTF.

How Can a Prepper Prep for the Poor?

Even if your Mutual Assistance Group intends to turn away all strangers (the outside poor), consider how you will deal with your own internal poor. To paraphrase Matthew 7:2, your policy toward “the poor” might just get applied to you too. If YOU became disabled or ruined, what strategies would you like to see in place in your group?

Perhaps have members pay into a Relief Fund (like a food pantry) to help with members too injured or sick to work, etc. Odds are, someone in your otherwise-healthy MAG will become poor. It could even be you.

Consider whether you might resort to Auctioning — distributing the impotent poor among your group members.

Consider how you might go about Binding Out orphans or even the stray working poor individual. For this to work, you need to assess your resources to see if you could support a new mouth to feed. Would his labor for you be worth the food he eats? Think about what work you might have around your homestead or BOL. It should be value-producing labor, not just busywork.

If your group finds itself with more poor than can be absorbed by Auctioning and Binding Out, you may need to set up your own Poor House or, better yet, a Town Farm to house them all. This endeavor will need to be organized to avoid waste. An overseer will need to be onsite to ensure the residents are not moochers.

Explored in Fiction

In my Siege of New Hampshire series, one of the grid-down realities I explored was what it might look like for a family and a community to deal with the less fortunate around them.

Burden or Opportunity?

The thing that put Town Farms and Work Houses out of business was the rise of industry. Factory owners built factory housing near the mills so workers would never be far from their jobs. Most work in the mills did not require high skills. (swap empty spools with full ones, etc.) Work in the mills was tough but better than the Town Farm. With the able-bodied poor flocking to the mills, Poor Houses devolved into mostly old-folks homes and asylums.

If you are of an entrepreneurial bent, consider that after an SHTF event, there will be a lot of unskilled labor available. Could YOU be like the 1800s mill owners and tap that resource to your advantage? If so, you and your unskilled laborers could both benefit.

Maybe you don’t own a water-powered mill (or perhaps you do). What could you and your crew of working poor do that other post-SHTF people needed? One idea that comes to mind is firewood. It is a consumable, required to cook and heat homes. Felling, bucking, splitting, stacking, and hauling are all labor intensive and low-skill tasks (off-grid too). If you have a large enough farm, how many farm hands could you reasonably support? Maybe they just work for room and board. Perhaps you share some of the harvest profits with them.

The laborers will be there. Could you turn them into a resource instead of a threat?

Conclusion

An SHTF event will probably not be a cathartic cleansing of the society of its riffraff: where only the hard-working preparedness-minded remain. There will still be poor people — actually, there will likely be MORE poor people. They won’t all be lazy moochers to be chased away with buckshot. They may be people from within your own group. The poor will be part of any “new world,” post-SHTF. Prepare for them. They might even prove to be an asset.

—