This is a post I did in the last year but seemed to have disappeared from the blog. I referred to it in my previous post about Sumac Tea, so I figured I should repost it. They are related, in that sauerkraut is a garden-growable, winter-storable source of Vitamin C.

Here is the “lost” post (with a few updates) —

If the trucks stopped resupplying the stores (for whatever reason) serious preppers know they will need to plant a “Crisis Garden” to produce their own sustainable food source. That’s the purpose for all those Seed Bank products.

Growing enough food to sustain you and your family through the winter would be challenging. Carbs and protein are necessary but many vitamins are also crucial to staying healthy. Growing vitamins is yet another challenge.

Vitamin C, for instance, is important for keeping your immune system strong. C also helps your body create collagen: THE primary protein in your body’s connective tissues. A shortage of vitamin C makes you more vulnerable to common illnesses. Even if you managed to dodge catching a bad cold, a C deficiency for just a couple months can bring on scurvy.

Scurvy?

Early symptoms of scurvy include anemia, pain, swelling, bleeding gums, listlessness. A grid-down situation is a really bad time to be weak, short of breath and listless. Left unaddressed, scurvy can progress to jaundice, spontaneous bleeding, teeth falling out, fever, convulsions, and eventually death.

Before modern vitamin pills (+/- 60 years ago), people got their vitamins from their food. In ancient times, peasants in northern climates faced the prospect of scurvy each winter because foods with vitamin C (greens) were not available in the winter. Peasants found a way without grapes shipped up from Chile, nor oranges from Israel, etc.

When men began long ocean voyages in sailing ships, they subsisted on hardtack and salt pork. Neither has any Vitamin C. As such, scurvy killed thousands of sailors every year.

In the “Age of Exploration,” when sailing ships were at sea for months at a time, the odds of returning home alive were not good. The danger was not so much the storms and prospect of shipwreck, but scurvy. For instance, in 1740, Commodore Anson left England with a crew of two thousand men for a round-the-world voyage. He returned with only seven hundred. Over half his crew died of scurvy within the first ten months.

The British realized that having a big navy was of little value if most of their sailors were sick (or dying) so they looked for a cure. Citrus fruits were known to help prevent scurvy but fresh citrus was not always in season and citrus fruits did not store very long.

There was no refrigeration in the 1700s. Everything aboard a ship had to be shelf-stable: such as salt pork and hardtack, washed down with grog. With that sort of diet, sailors got the two major macronutrients — proteins and carbs — plus hydration. (The grog was watered down to be only alcoholic enough inhibit algae growth in the barrels, but not enough make everyone drunk.)

The Admiralty tried different additions to the Spartan sailor’s diet. Most of them failed. Lemon juice was effective but spoiled too quickly for long voyages.

It turned out that the humble peasant food — sauerkraut — was the answer. It was high in vitamin C and kept for months.

When Captain Cook sailed on his Pacific journey (discovering Australia and New Zealand), his ship, Endeavour, was provisioned with three tons of sauerkraut! Cook was a shrewd judge of human behavior. Rather than order his men to eat the sauerkraut, he started serving it only at the officer’s table. Thinking it was some treat, his crew asked if they could eat it too. (Cook had three tons of it, so yes)

His crew was at sea for months at a time over three years. They ate a portion of ‘kraut every day. Captain Cook did not lose a single man to scurvy.

Sauerkraut, it turned out, was the ideal diet supplement. While sauerkraut was new to the Admiralty, the benefits were old news to poorer Europeans. Their diet wasn’t much better than a sailor’s. Central European peasants made sauerkraut to help get them through the winter. Koreans relied on their version of sauerkraut — kimchi — to get them through winter’s “Hunger Season”.

Sauerkraut enabled the British Navy to embark on long voyages without losing sailors to scurvy.

Self-preservation: Lacto-fermentation

Aside from being rich in vitamin C, a major benefit to sauerkraut is that it will keep at room temperature. Its acidic brine inhibits the bacteria that spoil regular foods. The result is that sauerkraut will keep for months. I just ate the last jar from the previous year’s harvest — one full year later. It was almost as good as the first jar. Our jars were stored in a cabinet in an earth-sheltered garage: not quite a root cellar but cooler on average than room temperature.

If you were in an extended grid-down situation, wouldn’t you want a food that kept for months without refrigeration AND contained crucial vitamins?

High C

Fresh cabbage, like many greens, has some traces of vitamin C. Sauerkraut has much more than raw cabbage because of the fermentation process. The microbes that create lactic acid also produce vitamin C as a byproduct. They also contribute some vitamins A and B.

How It Works

For centuries, people have known they could ferment cabbage into sauerkraut, even if they had no idea that lactobacilli existed. Fortunately, not knowing about the microbes does not stop them from working. To make sauerkraut, all you need is fresh cabbage and some salt. (How To, below) Two weeks later, you’ve got sauerkraut. Vitamins couldn’t be simpler.

Naturally occurring on growing cabbages, are four major types of bacteria. I won’t list their longish Latin names. You can google lacto-fermentation if you’re curious.

Two-stage Fermentation Process.

When you add the salt to the chopped cabbage, it expresses the water inside. This makes a simple brine. The salty water automatically inhibits most bacteria. A variety of salt-tolerant bacteria start the fermentation process. They make the brine slightly acidic. This discourages still more bacteria that might cause rot. A couple of types of Lactobacilli love the mildly acidic brine They convert sugars in the cabbage to more lactic acid. During the process, the bacteria are also making vitamins.

After two weeks at room temperature, the fermentation process is pretty much complete. You could leave the sauerkraut in its big crock in a cool place, ladling out portions as you need them. You could (as we do) package it into handy jars for storage.

DIY Vitamin C

Making your own sauerkraut is simple. It isn’t just something you do in autumn. You can make it anytime there are cabbages in the supermarket too.

Start with fresh cabbage and a non-iodized salt like sea salt or canning salt. The ratio is 3 tablespoons of salt to 5 pounds of cabbage. The ratio is not super-fussy but don’t stray too much. Too little salt can allow the rot-causing bacteria to stay alive and ruin your batch. Don’t skimp on the salt thinking you are making a healthier low-salt batch. The “good” bacteria need that salt. Too much salt just makes for salty-tasting sauerkraut. You can rinse it before serving. No harm done.

trimmed of outer (damaged) leaves and cores removed

1. Chop your cabbage into thin slices. This exposes more surface area to the salt and makes it more fork-friendly to eat.

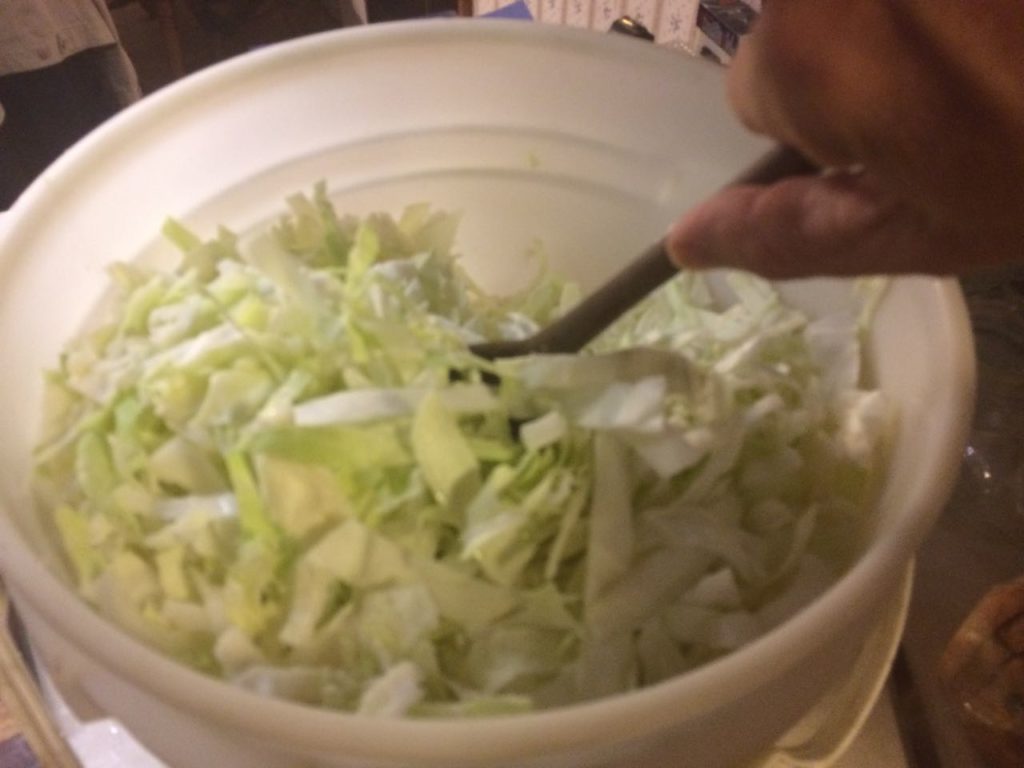

2. Sprinkle salt on the shreds as you put them into a plastic bucket or a ceramic crock that has a weighted disk that fits inside. Avoid aluminum, as it will react with the lactic acid. For me, a three-gallon food-grade plastic bucket just barely holds ten pounds of shredded cabbage before compression. As you’re adding your shreds, sprinkle some of the salt in, a layer at a time. That’s much easier than trying to stir a full bucket of shreds to mix in the salt dumped on the top.

3. Stir your bucket full of cabbage shreds and the salt you’ve been sprinkling as you go. This helps make sure the salt is evenly distributed among the shreds.

4. Press the weighted disk on top of the shreds. I have a dinner plate that is a fairly good fit within my bucket. I place a container of water on top (in lieu of my hand) for the weight. Press down on the plate to help squeeze out the air. Aerobic bacteria are bad. Compressed, your batch of kraut will fill about a quarter of the bucket.

5. Place the bucket somewhere with moderate temperature. A warmer place will make the fermentation go faster. A cooler place will slow it down. 65 degrees or so is ideal. Your sauerkraut will be fermenting for a couple of weeks, so someplace accessible for regular checking is good, but not underfoot.

6. Check. After a few days, you should notice that the brine will have risen up around the edges of your weighted disk. Pressing down on the disk periodically can help compress the sauerkraut and work out any stubborn air pockets. After a week, you should begin to smell the fermentation and see little patches of foam around the edges. You might see little floating dots of mold too, after a week or so. Any organic matter that is exposed to the air is vulnerable to mold. Not to worry. The mold does not mean your batch has gone bad. Just scoop off the mold with a spoon so it doesn’t multiply. Mold multiplies quickly, so regular checking and “thinning the herd” helps.

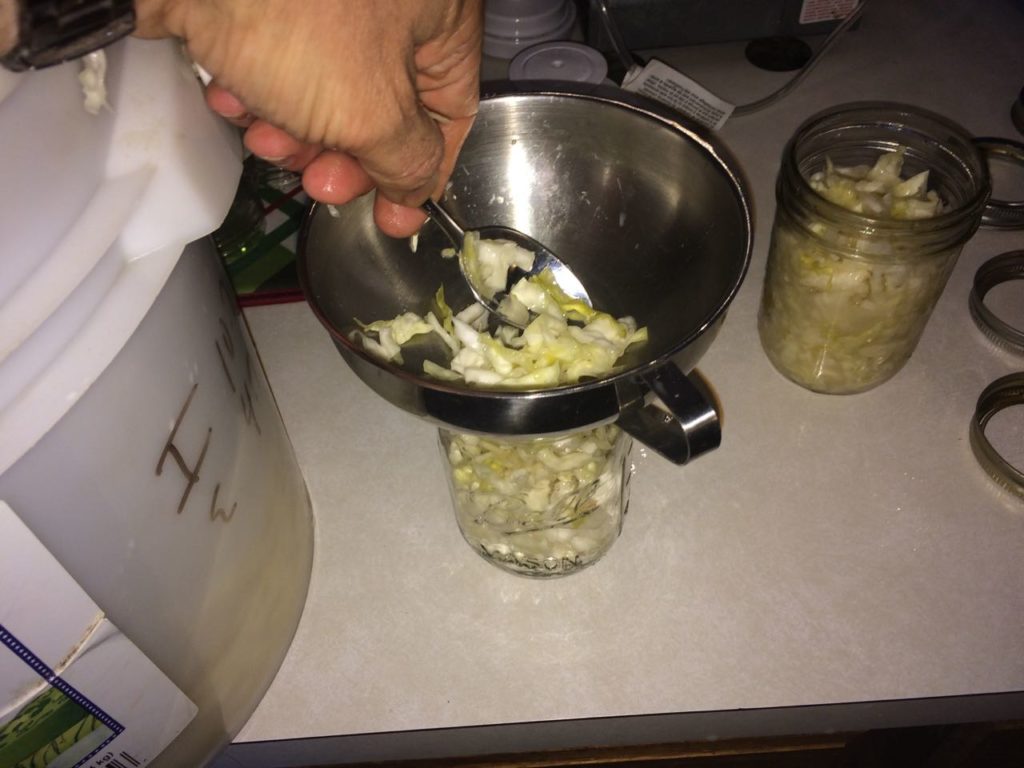

7. Pack. After two weeks, your batch should be sufficiently fermented and ready to be transferred to jars. Before you remove the weight and disk, scoop away any last bits of dried foam and any mold so they don’t fall down into the kraut when you take away the weight. They’re a pain to pick out of the shreds. You can leave them in there. The little visual dots of mold aren’t harmful (the lactic acid kills the mold) but specks tend to put people off.

Scoop the kraut into clean Mason jars. Pints are good for small family side dish serving. Quarts are good for larger recipe use. Pack tightly into the jars so that the brine rises up to within an inch of the jar rim. Packing squeezes out the air that gets in during packing. You may have some brine left after filling your jars with sauerkraut. Use that brine to top up any ‘dry’ jars.

Screw on lids for storage. Kraut does not need a hot water bath treatment like regular canning. The lactic acid is doing the preserving. Lately, I’ve been vacuum sealing my jars of kraut just to ensure a good seal for storage – and because I had rigged up a former airbrush compressor from my college days to serve as a vacuum pump. This isn’t strictly necessary. My first ever batch had no vacuum seal and was just fine. After all, they did not have little electric vacuum pumps aboard HMS Endeavour.

8. Store your jars in a dark and as cool of a spot as you can find, like a root cellar or a cool garage. Under 60 degrees, the fermentation process stops, so your kraut will stay crunchy longer. Over 60 degrees, the fermentation resumes within the jars. The longer the kraut ferments, the softer it gets and the stronger-tasting. I’ve had some that were warm for too long. They were edible, but the squishy texture was not popular with the family.

There you have it. Vitamin C you can grow in your garden and store for winter. You can ferment carrots, beets, turnip and of course, cucumbers with Lacto-fermentation. Plant some cabbage in your garden this spring. Make sauerkraut in the fall and be scurvy-free all winter! Or, make it right now. if you can buy cabbages. Who wouldn’t want to be scurvy-free?

As a side comment to this excellent article the lacto Bactria in fermented kimchee and sauerkraut will also help keep you healthy. Much like the “probiotics” folks seek out from yogurt (also a fermented food).

I know when I have a bit of the flu bothering me NOTHING knocks it out faster for me than a good Hot Bowl of Kimchee Soup and bed rest. Super Jewish Penicillin friends. You will smell of garlic and need a LOT of nose tissues but Flu BE Gone…

Might be handy if a serious flu situation comes around.

Good stuff