It’s oft repeated in prepper circles that a big EMP would send America back to the 1800s. It if did, what would life be like? Some historical sources from 1810 provides some useful lessons for what being back in the 1800s would be like.

After a prolonged grid-down scenario, “work” will look very different from how it does now. The vast majority of the jobs people earn their living at today, are either directly dependent upon the grid, or upon grid-dependent fossil fuels. Those jobs and that grid-supported economy would simply cease to exist. Think about your own job. If the power was out for 6 months or a year or longer, would your job still exist? If your job is gone, what will you do?

Let’s assume that The Event happened and that the survivors have moved past the raging gun battles and lawless Mad Max stage that many picture happening.The resources those survivors consumed every day (food, water, etc.) would have to come from either storage or be newly created.

We live in this storage-vs-creation dynamic today too, of course. You either have a million-dollar trust fund and don’t have to work, or you DO have to work to provide your ‘daily bread.’ Storage is finite. Work keeps producing. People will eventually have to work and make their daily bread.

While many people seem to find the prospect of living in 1810 terrifying, the people back then managed to get by with reasonably un-terrible lives. Some of them were reported to actually be happy. AND, without the

To see how different life was back then, I studied the records of a semi-subsistence farm in central Massachusetts. It seemed like a good place to look for life in the early 1800s. River Bend Farm seemed similar (enough) to what a prepper’s rural BOL would need to become after the stored buckets of freeze-dried foods ran out. The prepper family would eventually have to become farmers: creating new food for themselves. Studying River Bend Farm yielded several lessons for what a 21st century person might expect life and work would be like if America ever were thrown back into the 1800s.

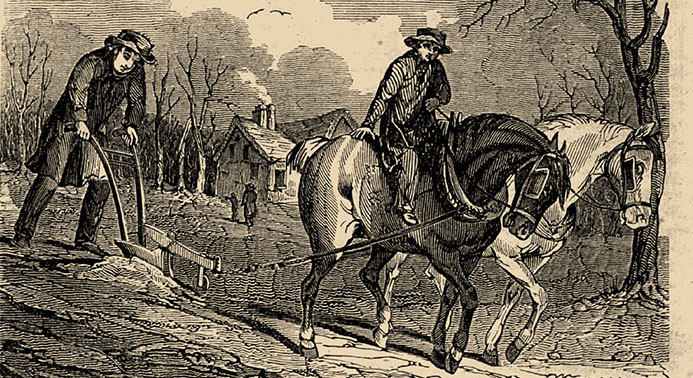

Lesson 1. Expect manual labor

So much is done for us today by either electric motors or fossil fuels that it has become easy for us not to notice how much work things take. A little motor grinds our coffee beans in the morning. An electric pump sucks water out of the ground to fill our coffee pot. The grid heats the element in our coffee maker, etc. etc. It’s become so common that we scarcely notice anymore. (That is, until it’s gone.)

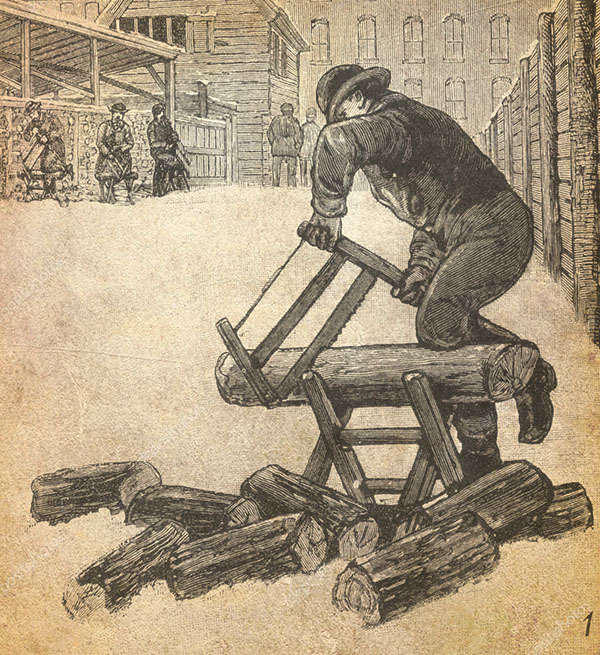

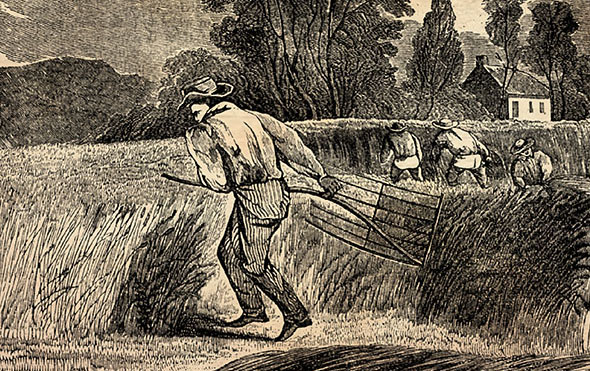

Back in 1810, most of the work was done by muscle power. (Yes, mills had waterwheel power but the average farm did not.) Rural folks labored from before sunrise to after sunset: almost never getting everything done that needed doing. Men worked in the fields, tended the animals, cut and split firewood. Men and women beat flax stalks and combed it into fibers that women folk spun that linen yarn that they then wove into ‘homespun’ fabrics. Clothes were washed by hand. Water was pumped and hauled by hand. Horses or oxen pulled the plow or the wagon. Men with scythes cut the grain. Men with flails threshed the grain. Men with saws cut logs into boards or timbers which other men assembled into houses or barns. Muscles did the work. Are you ready to do physical chores of an 1800s life?

Lesson 2. Expect to be more self-sufficient

The folks at River Bend Farm made things for themselves. They grew their own food: even if not absolutely everything they ate. They raised animals to provide meat and/or protein (milk, cheese, eggs). Eventually, they specialized in milk cows. They cut their own wood for heat and cooking. They built their own structures (usually with help, see point #3) fixed their own tools, wove their own baskets. The women spun their own yarn and wove their own fabric. If they needed something, they made it themselves. This was a time before factories and Walmart and Amazon Prime. After the EMP, the factories won’t be cranking out anything.

What can you do now? If the grid goes down for a long time, expect that you’ll be doing a lot more manual labor. A common bit of prepper advice is to ‘get in shape.’ This doesn’t mean body-builder-shape. Most people in 1810 did not have buff beach bods. What they were, however, was accustomed to doing manual labor. Bench-pressing 300 lbs. won’t come up much on the farm. Hauling buckets of water, armloads of firewood, wheelbarrows of dirt all day will be the norm. Improve your stamina. Do manual chores around the house for a full day. See how you fare. The experiment will likely tell you where you need to toughen up. Work on it.

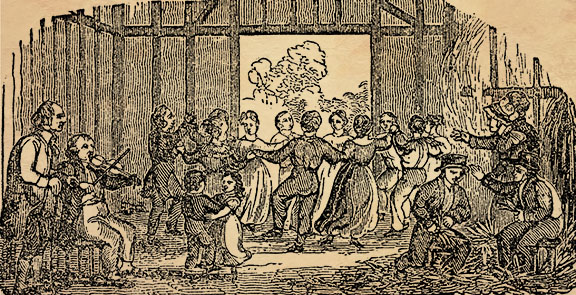

Lesson 3. Expect to engage in trade

Money was in short supply shortly after the War of Independence. (as it might be post-EMP) The local economy did not stop for lack of cash. No farm was an island. The folks at River Bend Farm regularly traded what they had in excess for other things they wanted or needed. They traded crops, produce, and handmade goods. One of the most commonly traded things was labor. They were a community by necessity. It took many hands to harvest a hay crop quickly or raise a barn. Whoever refused to help his neighbor could expect no help when his own need arose.

Trading with neighbors was necessary.

An unfortunate feature of our culture today is that the average person has become An Incapable — no longer able (or willing) to do much of anything for themselves. They spend their day earning an income doing some grid-dependent job. That income pays for someone else to do just about everything else for them. Odds are, since you’re reading this, you aren’t one of The Incapables and want to be even more self-sufficient.

What can you do? Do more yourself. Start out slowly if you have to. Plant a little garden — even if it’s in buckets on your apartment balcony — so you can learn to grow some food. Don’t call a plumber; fix your own leaky faucet. Change the oil in your car. If you’ve got the basics covered, kick it up a notch. Learn to hunt small game. Skin and clean them yourself. Cook it over a fire. Try grinding wheat (no electric mills) to make flour and then bake your own loaf of bread. Build a stool or chair out of wood. You don’t have to be a master at these tasks. An 1810 farmer’s asymmetrical carved wooden spoon still scooped soup. Your hand-made things don’t have to be perfect. The goal is functionality.

Shared labor from neighbors was the best way to get the job done quickly.

Trading Labor: One of the fascinating artifacts from River Bend was an account ledger book, in which the farmer recorded what he did for neighbors and what they did for him. Entries ran like: June 20th, 21st. helped P.Johnson butcher cattle: 2 days labor. or: June 24. H. Adams helped me cut and rake hay: 1 day. Each farmer kept his own account book, with matching entries. When a day’s labor was repaid, the record was crossed out in both books. Every farmer knew to whom he owed labor or goods and who owed him. When the hay needed to be brought in, or when a barn needed to be raised, it took a lot of shared labor for a short time. What would you have to trade?

What can you do? Odds are, you’ll have time/labor you can trade. In addition to that, plan on having something you can produce in excess of your household’s needs — something your neighbors need and aren’t producing for themselves. This takes some entrepreneurial thinking. If everyone else is growing zucchini, don’t grow more of that to trade. Few will want it. If no one around you is weaving baskets, make baskets. Look for and plan for ‘market opportunities.’

Lesson 4. Expect to make the best of what you have.

River Bend Farm sat on marginal soil that tended to be moist (being on a bend in the river and all). It was poorly suited to

What can you do? Assess what your BOL (or Bug In Location) has for strengths. Very few among us are going to have the perfect BOL (or BIL) that will supply all our needs. Realistically assessing your location’s strengths can help you specialize. If you’ve got a heavily wooded BOL, plan ahead to be a provider of firewood or lumber. If you’ve got a running stream, figure on a mill.

In all of this planning, though, keep in mind the realities market dynamics. If everyone around you has heavily wooded lots, your firewood won’t be worth much in trade. If everyone around you had goats and pigs and chickens, your meat rabbits probably won’t fetch much in trade. Consider your local market. Find a niche.

Lesson 5. Expect to do many different jobs.

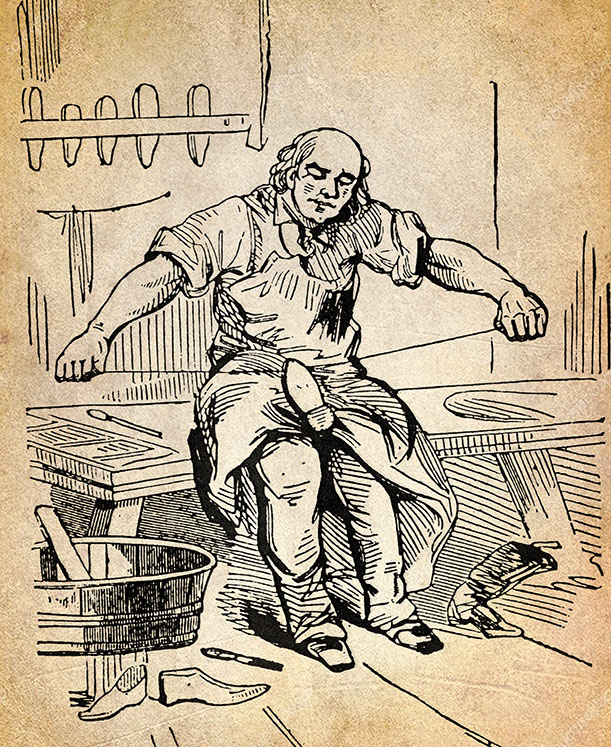

The men and women at River Bend were farmers most of the time but they also had many side gigs. They did day labor for neighbors, they assembled leather shoes in the winter and made wooden tools. The women at the farm braided rye straw for hats and spun yarn for the woolen mill and wove extra cloth of their own to trade with neighbors. Some farmers had a mill and pond. For a couple months the spring, when the streams were flowing strong, they would saw wood, grind grain, or full cloth. Another farmer had a blacksmith’s forge but he seldom had enough blacksmithing to keep him busy five days a week, all year long. He still had to be a farmer too. The local doctor farmed. There weren’t enough sick people to attend to eight hours a day, five days a week. Doctoring was his side gig.

The Industrial Revolution has conditioned us into thinking that “work” is doing one job, the same job, five days a week, for twenty years. If the grid goes down long-term, almost all of those mono-jobs will disappear. Would your job be one of them?

What can you do? Think about what sorts of side gigs you could do. Think of tasks might people need in a grid-down world: carpenter, doctor, mechanic, veterinarian, tanner. etc. Be ready to do one or more of them. Most people will be in DIY-mode (see #1 above) and not need the routine things done for them like sweep their sidewalks or rake their leaves. Even if they wanted you to do their mundane tasks, would they have anything to pay you for it? You’ll be better off if you can do something valuable on the side. Just make sure it’s not something that others are providing. Market saturation means a lower value.

Bonus Lesson: Expect Clutter

When you’re scraping by, spending every daylight hour just to keep the house warm, the family fed and the crops alive, tidiness becomes a luxury. City travelers in 1815 commented about the cluttered look of farms in the River Bend valley. Homes were usually in some stages of disrepair. Yards had junk in them. Children were usually dirty. This was understandable enough. The men and women of River Bend Farm were exhausted from long days of labor. Less crucial things were let go until later. If you’re a person with a low tolerance for clutter, plan ahead for how you’re going to keep your BOL organized and tidy when you’re bone-tired every day from working the fields until dusk. Odds are, your clutter tolerance may increase.

Conclusion:

While it is sometimes used in prepper articles as an OMG crisis that a grid-down America would be thrown back into the 1800s, it need not be so dire. Life back in 1810 was a lot more work but people managed. They were not bored to tears for lack of Facebook or video games or the latest ‘reality’ TV show. Quite a lot of them were happy. Those with ambition managed to thrive and achieve some degree of comfort. Plan ahead now and the 1800s might not be such a shock for you.

Mic: Good article. Thanks for taking the time to post it. I have printed it for my personal prepper manual and to give to a friend whom I hope will join me in prepping.

Hi Charles,

Thanks for the comment. Sorry for the slow response. Busy days. Being able to live (and maybe thrive) in an early 1800s environment seems like a great way to not worry so much about a grid collapse. I’m still working on some 1800s skills for just that reason.

— Mic

I say the grid going down wouldnt send us to the 1800s. It would send us back to the dark ages (no pun intended). Ask yourself: do you have a horse and the skills to shoe it? Do you know how to wash clothes with no washing machine or fix or make clothes by hand? Have a horse drawn plow? Do you have blacksmith tools and skills? How many people have the requisite hand tools? Those are just top of the head questions. I am sure there are hundreds more.

Experts estimate 85-90% of the US population would be dead within a year. The 1800s would be luxury

Hi Gulo,

People debate just how bad a grid-down world would be: the 1800s or Dark Ages. Personally, it seems more likely to be the 1800s, as there’s too much knowledge gained since the Dark Ages that won’t be instantly lost. Knowledge of bacteria, for instance, wrt hygiene. On a person-by-person basis, you’re probably right enough. Modern folk are (generally) quite clueless. That said, every individual does not have to have all skills. Even in the 1800s, not everyone had the skills of a ferrier, or a blacksmith. Some did, and traded for their services. There might be only one in a hundred folks nowadays who do have an 1800s-style skill, hand tools, etc. One blacksmith, for instance, can perform ironwork services for a lot of people who do not have the skills or tools.

Better to be one of those skills people, though. Develop a skill now, while it’s not mission-critical.

Lead that separates from brass will become currency/money (a medium of exchange) – .22 cal for squirrel hunting is cheap now & will be very valuable. In the Depression of the 1930’s, the deer population went down 75%! We in the south went back to post 1865 living after General Sherman torched GA.

Hi Hamp,

I tend to agree that separable lead/brass units will have barter power. Unlike silver or gold, the dual-metal units have an easily-understood practical value that, I think, will make them more attractive in a barter. I hear people say how you should never trade such units as they could be used against you. Do you worry about that?

Very good and valuable article, Mic. I am glad I am able to come over and have a read.

I’ve been soaking up and learning all I can from the information I’ve found on living simple such as those at River Bend. I appreciate what you’ve shared because I’m challenged to keep getting back to doing things simpler and being prepared for whatever may come. I haven’t arrived but continuing to go forward learning each day. I so relate to the fatigue at the end of the day but I’m sure nothing like the end of the day for River Bend folks. I obviously didn’t grow up in the era of the !800 but did live in a lot simpler environment with my grand parents.I learned a lot and miss it after being caught up in city life and the scenarios many are caught in.

I loved the cold water from the well and dipper to drink from in the well house. And we didn’t have indoor plumbing or a bathroom. It was the outhouse and a bucket for late nights. My grandparents raised chickens, pigs, dairy cows, and remember helping strain the cream. Long hours playing in the stream when work was done and helping my grandmother with the garden and canning. Also a good deal of time dodging cow piles helping my grandfather feed the cattle.

Everyone around the area came together & helped bale hay and pitch in during hog slaughter time.

I’ve got a lot of work to do and things to accomplish but there sure is joy and freedom in living and learning to do more for myself and less dependence on someone doing it for me or a machine.

Hi Cindy,

Thanks for the comments. Good to see that the white-list thing worked! Your experiences on your grandparents’ farm sound similar to mine. Lots of manual chores — and the outhouse! We’re actually well-blessed to have seen that lifestyle first hand. So many have not and can’t seem to imagine it as (not only survivable but) happy. Disentangling from the web of modernism isn’t quick or easy, but it can be done. There IS a lot of freedom (and from that, joy) in the simpler life. Keep up the good work.

Hey Mic,

I’m glad the white list did work.

I realize everyday how blessed I am to have experienced the lifestyle I did with my grandparents. I agree most would not appreciate the lifestyle today and find much happiness in it but it is doable. When I look back on times before now I can’t even remember much happiness, It’s just blank. If that is what modernization does I’m glad to be moving forward and beyond.

Definitely a lot of freedom and joy in the simple life.

Looking forward to learning more and going forward daily.